ABSTRACT

Hughes M, Caudrelier T, James N, Redwood-Brown A, Donnelly I, Kirkbride A, Duschesne C. Moneyball

and soccer – an analysis of the key performance indicators of elite male soccer players by position. J. Hum.

Sport Exerc. Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 402–412, 2012. In most sports, it is found that the important performance

indicators (PI’s) vary from coach to coach. Therefore, if sets of PI’s can be identified and clear operational

definitions defined, there is significant scope/benefit for consultancy and research, particularly in

commercially orientated sports such as soccer. The aim of this study was to use the unique opportunity of a

large number of performance analysts coming together to discuss this problem and its application to

soccer, and define sets of performance indicators for each position in soccer. In the early spring of 2011,

staff from 9 universities, from all over Europe, brought 51 level 3 Sports Science students to Hungary for an

Intensive Programme in Performance Analysis of Sport (IPPAS). The 15 staff, all experts in PA, had a total

of over 200 years of experience of PA between them. The most experienced ‘experts’ (N=5) acted as

mentors, introducing the area, defining the aims and managing the groups. The rest (N=10) and the 51

students were distributed evenly as possible across 7 groups, in which their aim was to define the key PI’s

for one of the positions in soccer. The positions used were:– Goalkeepers; Full Backs; Centre Backs;

Holding Midfield; Attacking Midfield; Wide Midfield and Strikers. In conclusion, 7 sets of KPI’S, were defined

for each of these classifications within 5 category sets: Physiological, Tactical, Technical –

Defending,Technical – Attacking, and Psychological. These KPI’s were different from position to position

within the team, particularly for the Goal Keeper. The KPI’s for the outfield players were very similar,

differing only in their order of importance. This enabled a ‘generic’ set of skills required for outfield players

in soccer. Key words: MONEYBALL, SOCCER, KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS, ELITE MALE,

POSITION

INTRODUCTION

For the notational analyst, team invasion sports such as soccer provide an ideal field for analysis as they

consist of a combination of individual techniques set within a team framework. Within Soccer, the use of

notational analysis enables coaches to improve aspects of their own team’s play, at both an individual or

collective level and also to interpret the actions of any future opposition.

Previous literature (Hughes & Franks, 2004) has proposed that notational analysis serves 5 purposes:

Analysis of movement

Reilly and Thomas (1976) created a methodology in order to analyse player’s movement and work rate

within the different playing positions/roles in a first division football team. A total of 51 (both home and

away) competitive games were analysed over a course of a season. Player’s movements were subdivided

into several distinct movement classifications. Individual movement characteristics of different positional

roles were established and associated modification of training strategies to be undertaken. This

methodological template has been refined and repeated in virtually all sports over the last 3 decades.

Educational use for both coaches and players

It has been shown (Franks, 1997) that any improvement in performance is a consequence of task related

feedback. Feedback can be provided before, during and after a skilled performance to both specific

individuals and to whole teams alike. Furthermore, Hughes (2004) identified the use of feedback as an

important component of the coaching process, and fundamental in the education of both players and

coaches.

Tactical evaluation

A tactical evaluation of soccer was undertaken by Yamanaka et al., (1997) who performed a computerised

notational analysis of 8 games in the 1994 World Cup Asian Qualifying matches. The respective playing

patterns of the teams were analysed, with a particular emphasis upon the Japanese national team. The

analysis assessed 32 actions of players in relation to an 18 cell division of the pitch. The authors showed

that Japan used more passes (p<0.01), more frequently used a clearing kick (p<0.05) and used dribbling

more as a tactic (p<0.05).

Development of a data base/modelling

It has been suggested (Garganta, 1998) that the development of a soccer model can be considered as a

mediator between a theoretical and an empirical field. The author explained how game modelling is

acquiring greater importance in order to analyse performance trends and to prioritise potential issue within

the training structure.

Technical evaluation

Partridge et al., (1993) developed a specialised computer analysis system, to undertake a comprehensive

technical evaluation of performance. 2 distinct levels of performance, the 1990 FIFA World Cup and the

1990 World Collegiate Soccer Championships were analysed using 38 key events entered in real time by a

trained analyst. From the results it can be inferred that collegiate coaches must be selective when selecting

World Cup teams as an appropriate model of performance as many differences do occur, which makes any

comparison invalid.

Games played at an International level are decided by small margins, the team that is superior in

physiological and motor abilities will have the advantage (Reilly & Holmes, 1983). This places a high

emphasis on a team at the elitelevel possessing high levels of technical ability.

Individual roles within a team framework

A soccer team consists of 11 individuals, all of which must undertake specific roles and associated

functions in each specific position in order to make a successful team. Although, players and coaches have

a universal knowledge of which technical components are required in order to play in each position there is

very little research to reinforce these concepts.

Table 1. Technical requirements of positions (Wiemeyer, 2003).

Position

Technical Requirements

Goalkeeper

Positional play, reaction times, calmness

Sweeper

Control of ball, organisational skills, defensive play

Central Defender

Defensive play, heading capabilities

Wingers

Physical conditioning, 1 to 1 play

Midfield (Defensive)

Defensive play, running, passing

Midfield (Offensive)

Technical skills, passing, creativity, shooting

Striker

Velocity, 1 to 1 play, shooting

Table 2. Individual tasks when in possession of the ball (Van Lingen, 1997).

Position

Technical Requirements

Goalkeeper

Positive distribution, communication

Sweeper

Circulate ball, switch play, play forward

Central Defender

Support build up play

Wingers

Good cross delivery, Score goals

Midfield (Defensive)

Don’t run with ball too much, switch play

Midfield (Offensive)

Add support. Get into scoring positions

Striker

Score goals, receive long balls

Table 3. Individual tasks when not in possession of the ball (Van Lingen, 1997).

Position

Technical Requirements

Goalkeeper

Prevent goals, organise defence, be aware

Sweeper

Give cover, close down space

Central Defender

Mark players, controlled defending

Wingers

Cut out crosses, tuck in to mark

Midfield (Defensive)

Control play, mark a player

Midfield (Offensive)

Support, defensive thinking

Striker

Keep opponents in front of you

A number of publications (e.g. Smith, 1973; Cook, 1982) have suggested the key characteristics needed to

play in certain positions within soccer. However, these publications are frequently based on coaches’

opinion; therefore much ambiguity exists between these opinions and the reported differences. Wiemeyer

(2003) interviewed 14 coaches, across varying participation levels in order to establish positional technical

demands. In only one case did all coaches agree of the exact functions of a position. However, the coaches

commonly agreed on many features across the positions (see Table 1). Van Lingen (1997) has suggested

that the tasks and functions of individuals within a team can differ according to whether a team has

possession of the ball or not (see Tables 2 and 3).

Frequently, authors (e.g. Reilly & Holmes, 1983; Dufour, 1993) have suggested the need for further

research in this area. As stated by Franks and McGarry (1996), the ability to provide information about

individual’s technical performance and the profiles of such players can significantly modify playing

behaviour and promote successful performance. Information about technical performance is also much

preferable to cursory comments made by coaches following competition (Franks and Goodman 1986).

Hughes and Probert (2006) undertook a technical analysis of playing positions within elite level

International soccer at the European Championships 2004. The qualitative data were gathered, post event,

based on the relative successful execution of techniques performed. Players were classified by position as

goalkeepers, defenders, midfielders or strikers. A comparison was also made between the technical

distributions of both a successful and unsuccessful team. Significant differences, using Chi Squared

statistical tests, (p<0.05) were found between the frequency distributions of all 3 outfield positions, but no

significant differences (p>0.05) were found between the accumulated means of technique ratings across all

of the performance indicators. However, individual variable analysis showed significant differences (p<0.05)

occurred between specific performance indicators across positions. The study showed that it is possible to

use qualitative assessments of skills in a quantitative way that is reliable, that coaches must take into

account the skills required by each position and hence be selective of which players play within those

positions. Furthermore, coaches must plan training sessions that are accurate to the specific needs of

individuals and their position within a team.

Williams (2009) suggested that improving the process of constructing operational definitions within

performance analysis and using a standard set of definitions for a sport would enhance the quality of data

sets and promote future research and analysis. Billy Bean (Moneyball, Lewis, 2003) defined these

processes and definitions for baseball and used them, with large objective databases, to recruit players

more efficiently and economically, and hence achieve success far in excess of the expectation of his club’s

financial standing.

However, in most sports, it is found that the important performance indicators (PI’s) vary from coach to

coach. Therefore, if sets of PI’s can be identified and clear operational definitions defined, there is

significant scope/benefit for consultancy and research, particularly in commercially orientated sports such

as soccer.

The aim of this study was to use the unique opportunity of a large number of performance analysts coming

together to discuss this problem and its application to soccer, and define sets ofperformance indicators for

each position in soccer.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Introduction

In the early spring of 2011, staff from 9 universities, from all over Europe, brought 51 level 3 Sports Science

students to Hungary for an Intensive Programme in Performance Analysis of Sport (IPPAS). The 12 staff,

all experts in PA, were also supplemented by 3 more experts from different commercial PA software

companies from Scotland, Europe and South Africa. The middle Sunday was termed ‘MONEYBALL and

SOCCER?’ and the question posed was “HOW DO WE OPTIMISE SCOUTING, PROFILING, PLAYER

DEVELOPMENT, AND HENCE TEAM AND CLUB MANAGEMENT?” The ‘experts’ had a total of over 200

years of experience of PA between them, ranging from 32 years to 3 years. It does not necessarily mean

that they were knowledgeable, but they must have learnt something to have survived so long in PA?

Procedure

The most experienced ‘experts’ (N=5) acted as mentors, introducing the area, defining the aims and

managing the groups. The rest (N=10) and the 51 students were distributed evenly as possible across 7

groups in which their aim was to define the key PI’s for one of the positions in soccer, so there were 8 or 9

in each group. The positions used were:

−Goalkeepers

−Full Backs

−Centre Backs

−Holding Midfield

−Attacking Midfield

−Wide Midfield

−Strikers

Each group elected their own Chair to keep order and a ‘scribe’ to record the findings of each think tank’s

brainstorming. Each group spent 2 – 2.5 hours discussing, debating and arguing over the key PI’s. Each

group then reported back to the whole assembly and their deliberations further discussed and debated.

Data analysis

The data gathered and presented were all in different forms and so we have tried to present them as a

coherent and logical set of themes. We are aware of how subjective a process this is, and how much

debate that each suggestion could initiate (starting with the 7 positions that were used, listed above). But

this is seen as a first step and, even if it is totally rejected and replaced with another set of key PI’s, then we

will have attained our objective?

RESULTS

Each group were given an open brief and so produced outputs that varied in presentation style. We, the

authors, then interpreted these outputs into the format shown in Table 4 – inevitably the production of this

table is an additional product of this subjective process (see Table 4).

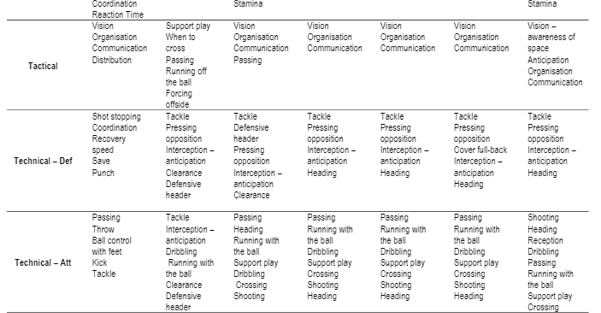

Table 4. The skill requirements (Key Performance Indicators) for the different positions in soccer.

DISCUSSION

The Key Performance Indicators (KPI’s)

It was surprising at first that the lists were virtually the same, just in a different order of priorities? But the

media often report that the ‘best’ players can play in any position, the similarity of the list reinforces these

subjective opinions. This is supported by the more quantitative approach of Hughes and Probert (2006).

There are differences in some of the positions, goal keepers are very different from the rest, and full backs

are different from strikers for example. But, given the similarities in these lists, it should be possible to

define a ‘generic’ list of the KPI’s for outfield players that define the skills required in soccer. The order of

priorityof these skills will vary from position to position, as shown in Table 4.

Despite the literature present in this field of notational analysis, there is an obvious opening for further

research to be conducted. Reilly and Holmes (1983) identified that a further study could incorporate an

analysis of skill performance within a competition context. Luhtanen (1988) also recognised how, by using a

similar notation system to his own, an evaluation of individual and team skills in match conditions could

occur.

The need for further research in this area was also highlighted a long time ago by Dufour (1993) stating that

“a techno–tactical profile may be generated in relation to an ideal profile corresponding to players place and

function in a team” (p.165).

As stated by Franks and McGarry (1996), the ability to provide information about individual’s technical

performance and the profiles of such players can significantly modify playing behaviour and promote

successful performance. Information about technical performance is also much preferable to cursory

comments made by coaches following competition (Franks & Goodman, 1986). The recording of events in

some coded form can help such coach observations to be formed, especially by defining each skill

performed as successful or unsuccessful (Franks & Goodman, 1986).

If an accurate analysis of the technical attributes of each player position was able to be established then

the results could significantly influence team selections and coaching sessions (Hughes & Probert, 2006),

and tactical decisions that are to be made by coaching teams, before and during matches. However, within

the literature, there are very few examples of technical analysis, in particular skill analysis, involving

association football. In this respect, the work of Hughes and Probert (2006) was innovative in two ways:

i)By analysing at the exact technical requirements of each position.

ii) By using qualitative data within a quantitative system.

The aim of this study was to analyse every individual’s technical ability that competes in the European

Football Championships of 2004. This measure was based on a subjectively drawn continuum that

analyses a player’s technical movement throughout the game. It was shown that technical differences

occur between player positions and between successful and unsuccessful teams. Perhaps studies of this

nature, based on qualitative assessments of the skill levels in each action, rather than counting the

frequencies of the actions, is the way forward for Performance Analysis and Notational Analysis in

particular?

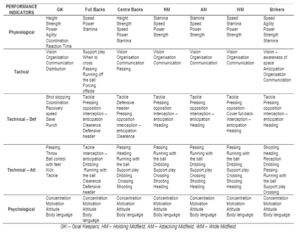

Table 5. Lists of KPI’s for the Goal Keeper and a generic list for outfield players.

PERFORMANCE INDICATORS

Goal Keeper

GENERIC

Physiological

Height

Strength

Power

Agility

Coordination

Reaction Time

Height

Strength

Speed

Power

Stamina

Agility

Tactical

Vision

Organisation

Communication

Distribution

Support play

When to cross

Passing

Running off the ball

Forcing offside

Vision

Organisation

Communication

Technical – Def

Shotstopping

Coordination

Recovery speed

Save

Punch

Tackle

Pressing opposition

Interception – anticipation

Clearance

Defensive header

Clearance

Technical – Att

Passing

Throw

Ball control with

feet

Kick

Tackle

Shooting

Heading

Reception

Passing

Dribbling

Running with the ball

Support play

Crossing

Psychological

Concentration

Motivation

Attitude

Body language

Concentration

Motivation

Attitude

Body language

Every coach and analyst will have their own views on the relative importance of the 5 categories of KPI’s.

Most importantly, they should be aware that they will be able to change the Physiological and Psychological

KPI’s, but perhaps not as much as they would like. But speed, strength, stamina, etc., can be improved by

specific training, linked with specific goals and compared to peer aggregated values (see Hughes &

Bartlett, 2002). Similarly, changes in the Psychological KPI’s are possible given correct training and

directed practises. Obviously these changes, in all sets of KPI’s, will be more effective and profound if

applied to younger players.

Every coach and analyst will also have their own views on the relative importance of the order of the skills

within the categories of technical and tactical KPI’s. But, and most importantly, they should be aware that

they will be able to change these skill sets in the Technical and Tactical KPI’s, but perhaps not as much as

they would like. But all skills can be improved, even for mature players, by specific training, linked with

specific goals and compared to peer aggregated values. The attitude, in a lot of clubs in Britain, is that

players have skill or do not, and so practising those skills is ‘de rigeur’. Kevin Keegan, European Footballer

of the Year 1978 and 1979, whilst playing for Hamburg in the Bundesliga, was labelled a ‘workhorse’

because he used to stay on and practise his skills after training. So the message is that instead of going to

the golf course to practise your golfing skills, stay at the club and hone your soccer skills.

Measuring subjective assessments

The Physiological and Psychological KPI’s can be measured objectively, reliably and accurately, but

assessing skill execution is a trickier task. Hopefully the data presented in Table 4, the order of KPI’s within

each category set for each playing position in the team, will be accepted and used by analysts, engaged in

research and/or consultancy work with professional or non–professional clubs, to create the notation

systems to gather data about performances. This could mean that a number of analysts would be using

systems based on the same category sets and would mean that they could be sharing data. This would

necessitate common sets of operational definitions for the actions and also the skill rating for each action.

But if not, they, or the coaches with whom they are working, may redefine the order of these skills, or define

their own sets – but they too should carefully define their operational definitions otherwise they may

compromise their reliability.

Having defined the operational definitions of a pass, tackle, running with the ball, dribbling, etc., the more

tricky task is to rate the level of execution of that skill in a consistent, reliable and accurate manner. The

method used by Hughes and Probert (2006) is shown in Table 6, this relatively simple and they showed

that, with considerable training and practise, it was reliable and accurate.

Table 6. Continuum of technique ratings (Hughes and Probert, 2006).

Rating

Operational Definition

+3

Excellent technique performed under pressure

+2

Very good technique performed under slight pressure

+1

Good technique performed under no pressure

0

Average, standard technique

-1

Poor technique performed under pressure

-2

Very poor technique performed under slight pressure

-3

Unacceptable technique performed under no pressure

Where to next?

If these sets of KPI’s are to be adopted by numbers of analysts throughout the sport of soccer, then the

operational definitions of the actions, and the subjective rating system, must be agreed. Perhaps further

research can target this as a piece of work to be done soon. If we can show the way with soccer, then

analysts working in other sports can follow this lead and define the sets of KPI’s that are most important in

each of their respective sports.

CONCLUSIONS

By bringing together a large group of Performance Analysts, 7 general classifications of positions in a

soccer team, and sets of KPI’S, were defined for each of these classifications within 5 category sets. These

KPI’s were different from position to position within the team, particularly for the Goal Keeper. The KPI’s for

the outfield players were very similar, differing only in their order of importance. This enabled a ‘generic’ set

of skills required for outfield players in soccer, bearing in mind that priorities of these skills will differ from

position to position.

It is recommended that further research pursues the operational definition of the skills, and also finds a

method for rating the execution of these skills, so that both can be identified reliably and accurately.

Perhaps studies, based on qualitative assessments of the skill levels in each action, rather than counting

the frequencies of the actions, could be the way forward for Performance Analysis and Notational Analysis

in particular?

By : MICHAEL HUGHES, TIM CAUDRELIER, NIC JAMES, ATHALIE REDWOOD-BROWN, IAN DONNELLY, ANTHONY KIRKBRIDE, CHRISTOPHE DUSCHESNE